Design Process

Summary

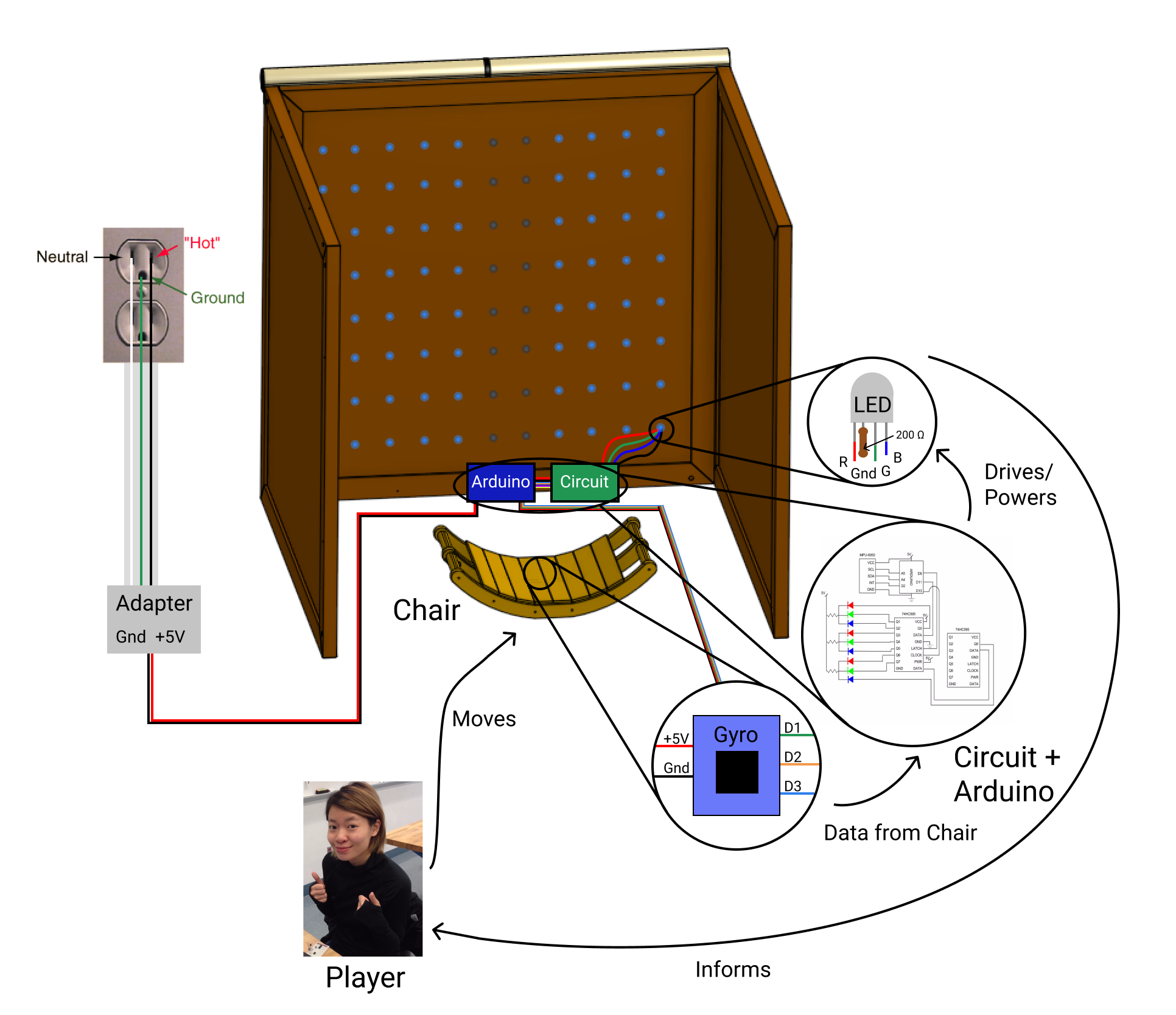

For this Principles of Engineering course at Olin College of Engineering, our team, Think Inside the Box, had the objective of designing and fabricating an interactive Cube-Runner inspired game. The player sits in a chair, which is embedded with tilt sensors and stationed inside a responsive cube integrated with LED “stars” which react to the user’s tilting (system schematic shown below). The player must navigate through gaps in approaching walls of light by tilting the tippy chair to the left or to the right as they accelerate through space.

Our team of four was given just over seven weeks (or 3.5 two week sprints) to design, develop, and execute our idea and create a fully integrated interactive game.

We started this project knowing that we had similar goals for our POE project, but without a solid idea of what we wanted to build. We knew we wanted to build an experience that would be immersive, and we all agreed that we wanted to get better at disciplines of engineering that we were less comfortable with. We also agreed on a major goal of creating a project that would feel polished at the end of the semester, knowing that this meant we would all have to level up our fabrication skills.

Prototype 1.0 (Sprint 1)

Our initial project idea was a biofeedback “sensory enhancement” box that would measure your heartbeat and other biometric data and then reflect that data back to you through the environment in the box. The box environment would appear larger on the inside through our inclusion of two way mirrors to create an infinity room. As we pushed through this idea we worried that since there was no concrete goal of being in the box, it would be difficult to make it the engaging and immersive environment we wanted to create in the limited time that we had. We also struggled with sourcing mirrors that were not damaged and within budget. After a few quick cardboard prototypes at different scales revealed that the idea was infeasible, we decided to change our direction.

Prototype 2.0 (Sprint 2)

We pivoted to the idea of an immersive game, giving our users a clear goal, and our team clearer metrics to determine our success. At this point, we were already three weeks into the project, so it was a pretty significant pivot and we wanted to figure out a way forward quickly.

Our first idea was to have a lightproof box with walls that would light up and give the user an impression of exploring a maze. This idea was exciting to us, but looking back we didn’t fully flesh out the user experience, which would lead to our second pivot. The maze idea required a two-axis tilt chair and four walls of light that would provide an interface to the maze. We kept running into issues with how to communicate our location to the user, and all the testing feedback we got indicated confusion from potential players. We created a prototype that communicated the maze via light as we had planned, but found that we needed to give users a laptop display of the maze in order for the game to be playable. At this time in our design process, we were also struggling with cost issues related to fabricating a box with five sides in a cost effective way. We knew we would have to make some changes.

Prototype 3.0, Final (Sprint 3 and 4)

We iterated on our game idea until we landed on an immersive version of cube runner, where the player sits on a chair that can tilt to control their motion along a single horizontal axis. We also adjusted our frame design to have three solid sides with a convertible fabric roof and final side. This design translated to less material and a more comfortable entry to the box for our players. It was also an appropriately simple game for us to build at scale, from scratch, in what ended up being more like a month.

You can see our MVP working below, with the player passing through the gap between blocks at first, and then hitting the wall on the second pass. We will update this video after the final period to show our game working in the completed frame.

Lessons from Prototyping

As we moved through our pivots, we had some issues with the realities of prototyping a large immersive game. We had prototyped the frame with cardboard, and that gave us good information that we could act on and use to inform our design iterations.

Prototyping the game and user experience proved to be more difficult. We quickly created small prototypes of the game, but in order to understand how it would work on a large scale, we would have to build it on that scale.

This led to our team focusing largely on fabrication at the cost of integrating systems. While we recognized the importance of integrating early and often, it was hard to simulate the experience without completely building our final product. In the end this worked out in our favor, but combined with our late start we had a hard time following along with the structure of POE as a class and hitting good integration targets for our design reviews.

Takeaways

One of the main things we learned as a team was that scale adds significant challenges in terms of both budget and time. It’s very easy to prototype a chain of 8 LEDs or inserting five pieces of fiber optic cable through holes in a board. It is less easy to fabricate hundreds of LEDs into a matrix, or poke thousands of fiber optic cables through a board. Our scale required us to do tasks hundreds of time to produce our project at scale, and this meant we needed more materials and more time than we had originally budgeted.

In addition to this challenge, our pivots meant that no amount of careful planning and budgeting could erase the challenges we encountered. In the case of the fiber optics that we originally planned to use to deliver light -- in the shape of constellations -- through the walls of our box, we planned out how much we would need for our first prototype and then ordered that amount (which took two weeks to ship from China) with some wiggle room. When we changed our project to incorporate a game that would essentially need an even distribution of around 1000 light points (pixels) per wall. This was not going to be possible with the amount of fiber optics we had ordered, so we ended up making a matrix of hundreds of LEDs to illuminate these pixel holes. The end product was still beautiful, but quite different from our careful original planning.